Do you ever wonder why certain scents appeal to you while others don’t? It turns out that our preferences for smells are deeply rooted in our brains. Barani Raman, a professor of biomedical engineering, and Rishabh Chandak, a recent graduate, conducted a fascinating study on locusts to understand how the brain encodes scent preferences and learns from them.

Their research, published in Nature Communications, sheds light on how our ability to learn is influenced by what we find appealing or unappealing. For locusts, their sense of smell is crucial for finding food, mates, and sensing predators. Neurons in their antennae convert chemical cues into electrical signals, which are then processed by neural circuits in the brain.

Raman and Chandak focused on studying how neural signals are patterned to produce food-related behavior in locusts. They discovered that certain odors triggered innate behaviors, while others did not. The locusts showed a preference for scents that resembled grass and banana, while they were less fond of scents that resembled almond and citrus.

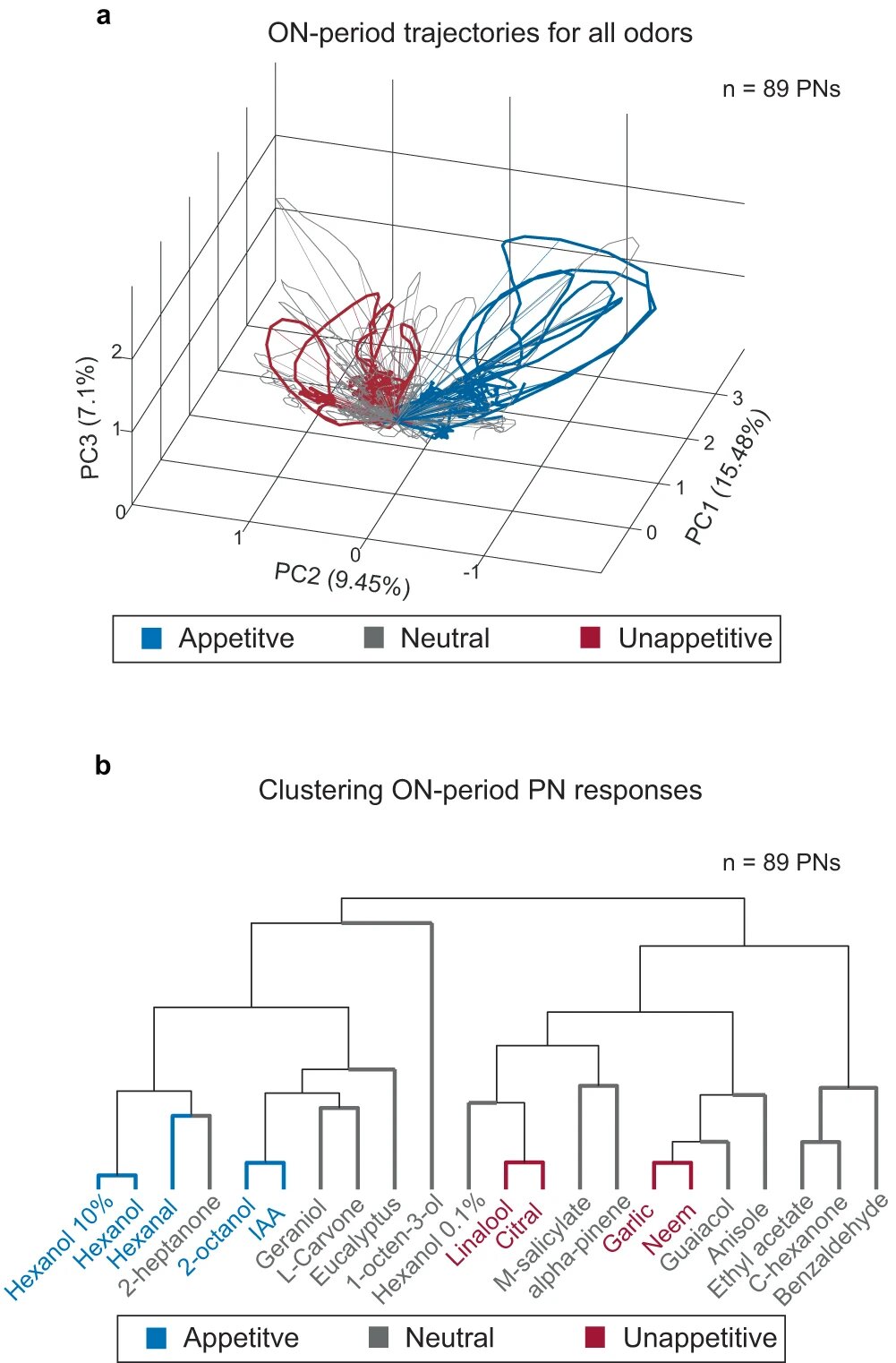

To understand why some odors were more likable than others, the researchers exposed hungry locusts to different scents and measured their neural responses. They found that the neural responses correlated with the behaviors triggered by each odor. In other words, they could predict the locusts’ behavior based on their neural activity.

Intriguingly, some locusts initially showed no response to any odors. To see if they could be trained, Raman and Chandak used a conditioning approach similar to Pavlov’s famous experiment with dogs. They paired each odor with a food reward and found that the locusts associated appealing scents with the reward. They also discovered that the timing of the reward during training was crucial.

Training with unpleasant stimuli actually made the locusts more responsive to pleasant scents. This paradoxical observation led the researchers to develop a computational model that explained how innate and learned preferences for odorants could be generated in the locust olfactory system.

“This all goes back to a philosophical question: How do we know what is positive and what is negative sensory experience?” Raman pondered. “It appears that sorting information in this fashion happens as soon as the sensory signals enter the brain.”