Prepare to be amazed by the incredible story of Takakia, a 390-million-year-old moss that calls some of the most remote places on Earth its home. This ancient moss, found in the icy cliffs of the Tibetan Plateau, has captured the attention of scientists who embarked on a daring expedition to study its DNA and understand how climate change is affecting its survival.

Published in Cell, the groundbreaking results reveal that Takakia is one of the fastest evolving species ever studied. However, despite its remarkable adaptability, it may not be evolving quickly enough to survive the challenges posed by climate change.

Takakia is a tiny moss that grows slowly and can only be found in small patches in the Tibetan Plateau, as well as in Japan and the US. The dedicated team of researchers embarked on 18 expeditions, scaling the towering peaks of the Himalayas to reach Takakia’s 4,000-meter-high habitat. Their mission was to unravel the mysteries of this living fossil.

“In the Himalayas, you can experience four seasons within a day,” says Ruoyang Hu, a plant biologist and co-expedition leader from Capital Normal University in China. “At the foot of the mountain, it is sunny and clear. When you get to the halfway point, there is always a light rain—it feels like you’re walking in a cloud. And when you get to the top, it snows and it’s very cold.”

The team faced numerous challenges, including the need to climb the remaining part of the journey as only half of the road was accessible by vehicle. But their efforts paid off as they successfully sequenced Takakia’s genome, shedding light on its incredible ability to adapt and survive.

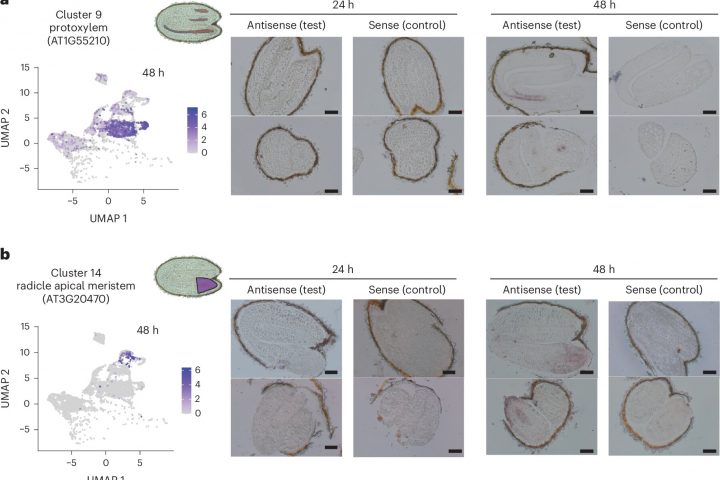

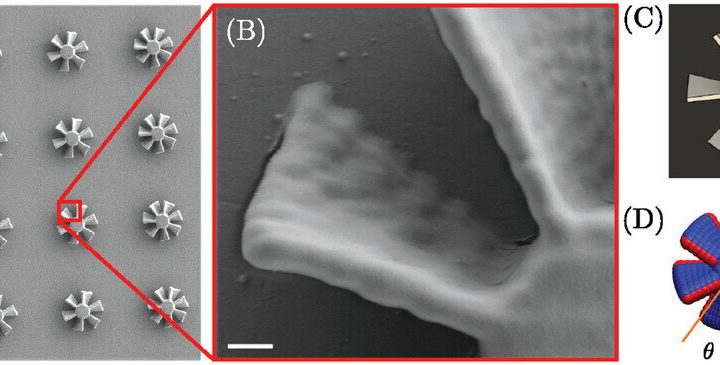

Through their research, the scientists discovered that Takakia possesses an extensive genome that has evolved over generations to excel at repairing DNA damage and recovering from UV radiation. This remarkable moss has developed a flexible branching system that allows it to grow in different locations, forming a network structure that can withstand heavy snowstorms.

Sequencing Takakia’s genome also put an end to a long-standing debate about its classification. “People wondered, is it really a moss? Or is it something like an alga or a liverwort? Because it has a combination of ancient traits,” says Ralf Reski, a plant biotechnologist at the University of Freiburg in Germany. “But our work shows that it’s a moss.”

While Takakia’s genome has undergone significant changes over time, its physical appearance has remained largely unchanged. This intriguing finding opens up new avenues of study, exploring the relationship between evolving genomes and static morphology.

Examining Takakia’s environment, the team observed alarming trends. Satellite weather data revealed a steady increase in temperature, causing the glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau to melt rapidly. The moss is also experiencing higher levels of UV radiation than ever before.

In laboratory experiments, the researchers discovered that the current level of UV radiation is lethal not only to other plants adapted to harsh environments but also to Takakia itself. Furthermore, the moss’s population has been dwindling, with a decrease of approximately 1.6% per year in Tibet.

Based on their predictions, suitable habitats for Takakia will shrink to a mere 1,000–1,500 square kilometers worldwide by the end of the 21st century. The authors sadly conclude that the moss is unlikely to survive another 100 years.

In an effort to save Takakia from extinction, the authors propose raising awareness about lesser-known species like this ancient moss. They also suggest an international collaboration to pool resources for continued research and protective measures, such as cultivating Takakia in a laboratory.

“Plant scientists cannot sit idly by. We are attempting to multiply some plants in the laboratory and then transplant them to our experimental sites in Tibet,” says Yikun He, a fellow plant biologist at Capital Normal University. “This may be the dawn of the recovery—or at least a postponement of extinction—for Takakia populations.”

As we reflect on the fate of Takakia, it serves as a powerful reminder of our responsibility to conserve and restore biodiversity. “We need to not only focus on those charming animals such as the panda, polar bear, and the white dolphin, but also pay close attention to these rare and little species,” urges Hu. “They are more vulnerable under climate change, such as our moss Takakia.”

Reski adds a thought-provoking perspective, “We humans like to think that we are on top of evolution. But the dinosaurs came and went, and so might humans, if we are not careful with our planet. Takakia may die because of climate change, but the other mosses will survive, even if we humans cannot. You can learn a lot from the simplest plants about the history of this planet, and maybe the future.”