Pigs are not only highly intelligent, but new research suggests they may also possess empathy towards their fellow group members, offering help when needed. However, scientists are still unsure whether this behavior is truly selfless or driven by specific goals.

To investigate this phenomenon, researchers from the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology in Germany and Austria’s University of Veterinary Medicine Institute of Animal Welfare Science conducted a study on helping behavior among social groups of domestic pigs. Their findings, titled “Spontaneous helping in pigs is mediated by helper’s social attention and distress signals of individuals in need,” have been published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

In the wild, animals often come to the aid of their distressed group members, defending them against predators or freeing them from traps and snares. However, there is ongoing debate as to whether this helping behavior is truly empathic or driven by selfish motives.

Previous experiments involving rats, mice, and ants have yielded inconclusive results due to concerns about the experimental designs and assumptions about the distress levels of trapped individuals. This new study aimed to address these issues by developing a new paradigm that allowed the pigs to exhibit a range of responses through increased behavioral flexibility. The researchers designed a test in which a pig could open a door to release a trapped fellow pig, incorporating pre-testing group socialization and location familiarization measures.

The study involved 78 newly-born German Landrace pigs from Germany’s Experimental Pig Facility at the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology. After weaning, two pigs were removed for medical treatment, and one pig died naturally. The results are based on the 75 remaining subjects who completed the study.

Socialization and familiarization

The research team divided the young pigs into four cohorts, each consisting of two social groups. At 28 days old, the groups were reshuffled, ensuring an equal balance of sexes and including two to four littermates from each contributing litter. The social groups were housed in neighboring pens, allowing them to hear and smell each other but not see or physically interact.

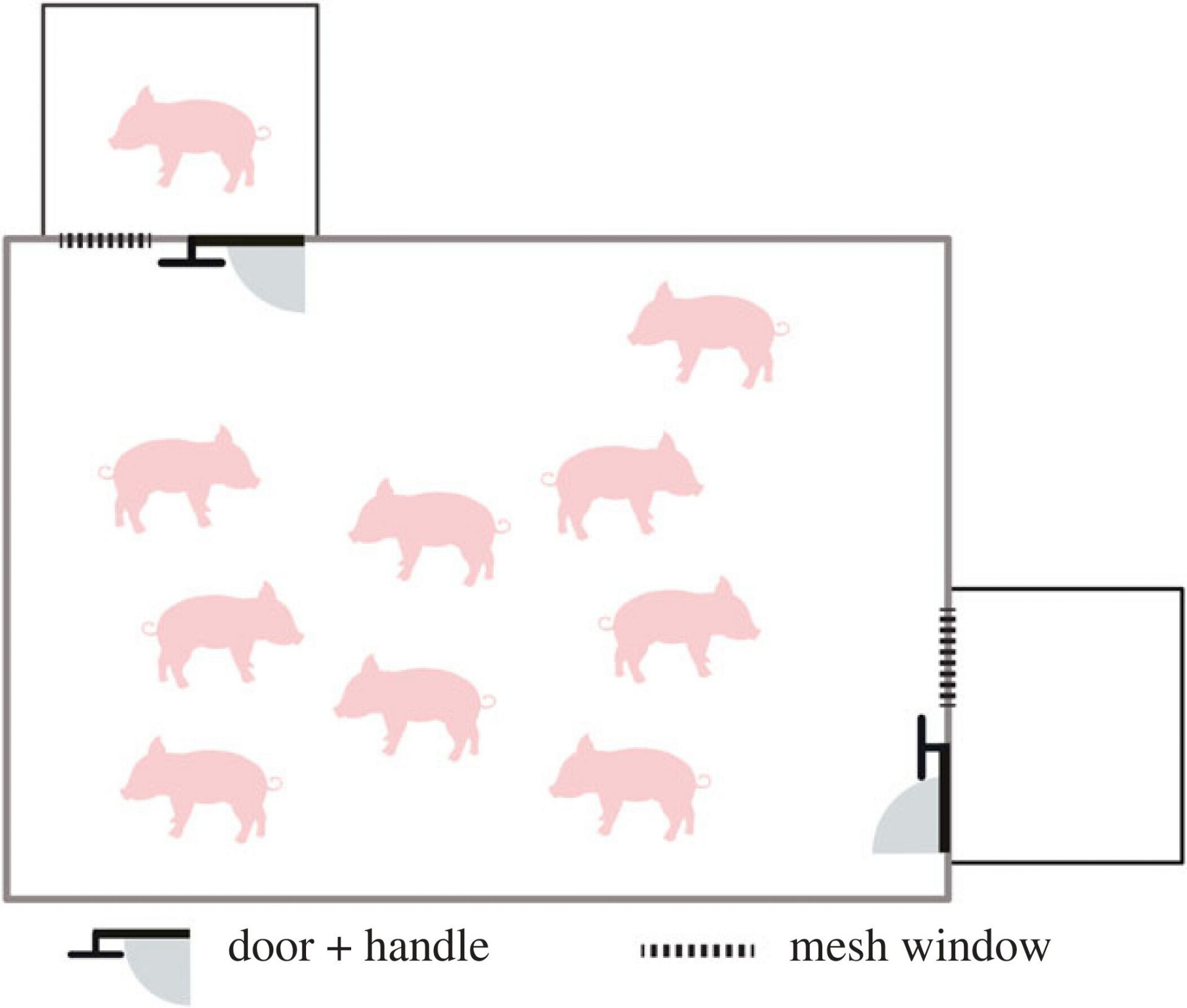

The pigs were then familiarized with two new compartments adjacent to their home pens. These compartments had open-top designs and a door-opening mechanism that the pigs could operate with their snouts.

Before the testing phase, the pigs were given multiple opportunities to explore the compartments. After each familiarization session, any pigs still inside were gently led out, and the doors were closed once the pigs lost interest for at least 10 minutes.

Pre-testing and testing

The pre-testing phase followed a similar process, but with the addition of isolating a designated pig in a separate room for five minutes while monitoring the rest of the group. This separation typically induced stress in the pigs, characterized by squealing, screaming, and escape attempts. Each pig took turns as the designated individual.

If none of the remaining group members opened the compartments during pre-testing, the designated pig was placed inside one of the compartments without any contact with the rest of the group. If a group member opened a door before the designated pig was placed inside, the compartment was checked for emptiness, and a five-minute wait followed before the test trial began.

During each test trial, the trapped pig could hear, smell, and see the group members through a mesh window, which also allowed limited physical contact. The second compartment remained empty as a control.

The test trial ended either when a group member opened the door to release the trapped pig or after 20 minutes with no help. However, the researchers noted that distress signals were not always necessary for helping to occur. In one instance, a trapped pig exhibiting distress was released by a researcher after three minutes without assistance for ethical reasons.

Results

Out of the potential helpers, 37 pigs (49%) opened doors during the pre-testing separation exercises, but only nine of them also opened the door during testing to help a trapped pig. Among the pigs that opened an empty compartment’s door during a test trial, only nine also helped a trapped pig. Overall, 64 trapped pigs (85%) received help from 33 group members (44% of the potential helpers), with each helper being the first to open the compartment door.

The researchers also found that potential helpers spent more time looking at the window of the test compartment than the empty compartment. However, they noted that the majority of trapped pigs produced distress signals that should have been detectable without looking through the window, suggesting that the helpers’ behavior could also be explained by more selfish motives.

In conclusion, the researchers observed that pigs who helped others visually assessed the situation before offering assistance. Distress signals from trapped pigs increased the likelihood and speed of receiving help. However, they emphasized the need for further studies to gain a deeper understanding of pigs’ motivations for spontaneous helping.