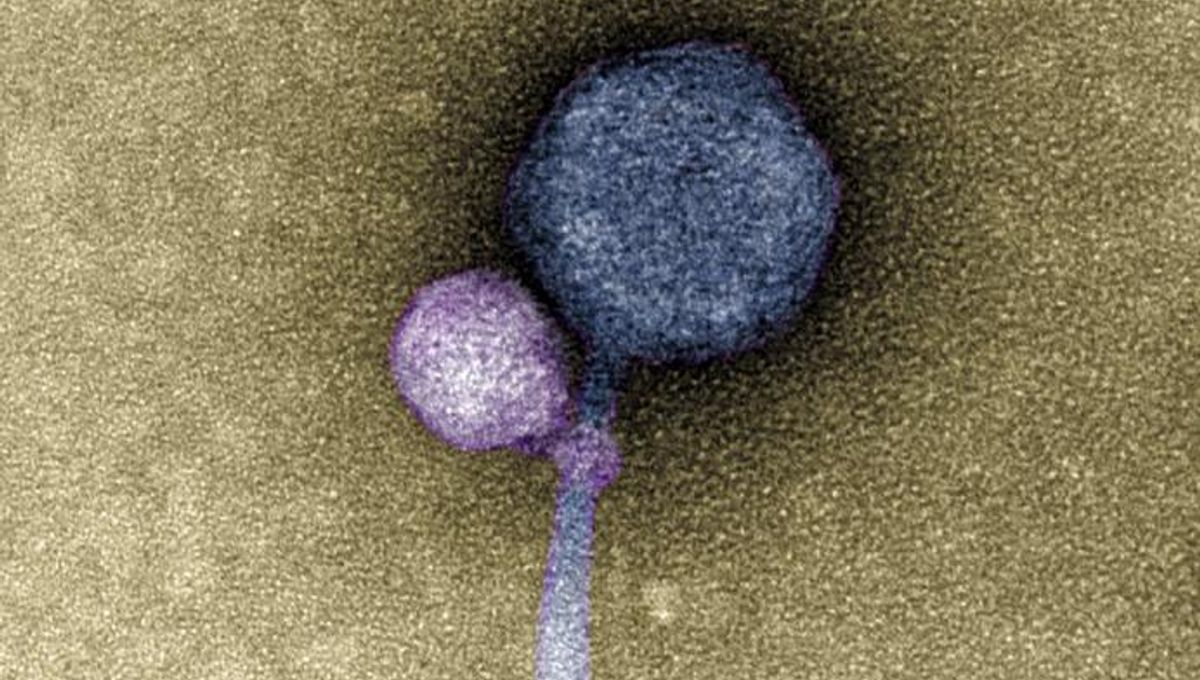

Prepare to be amazed! In a groundbreaking discovery, scientists have observed a virus attaching itself to another virus. “When I saw it, I was like, I can’t believe this,” exclaimed Tagide deCarvalho, the first author of the study. This is the first time anyone has witnessed a bacteriophage, a virus that infects bacteria, latching onto another virus.

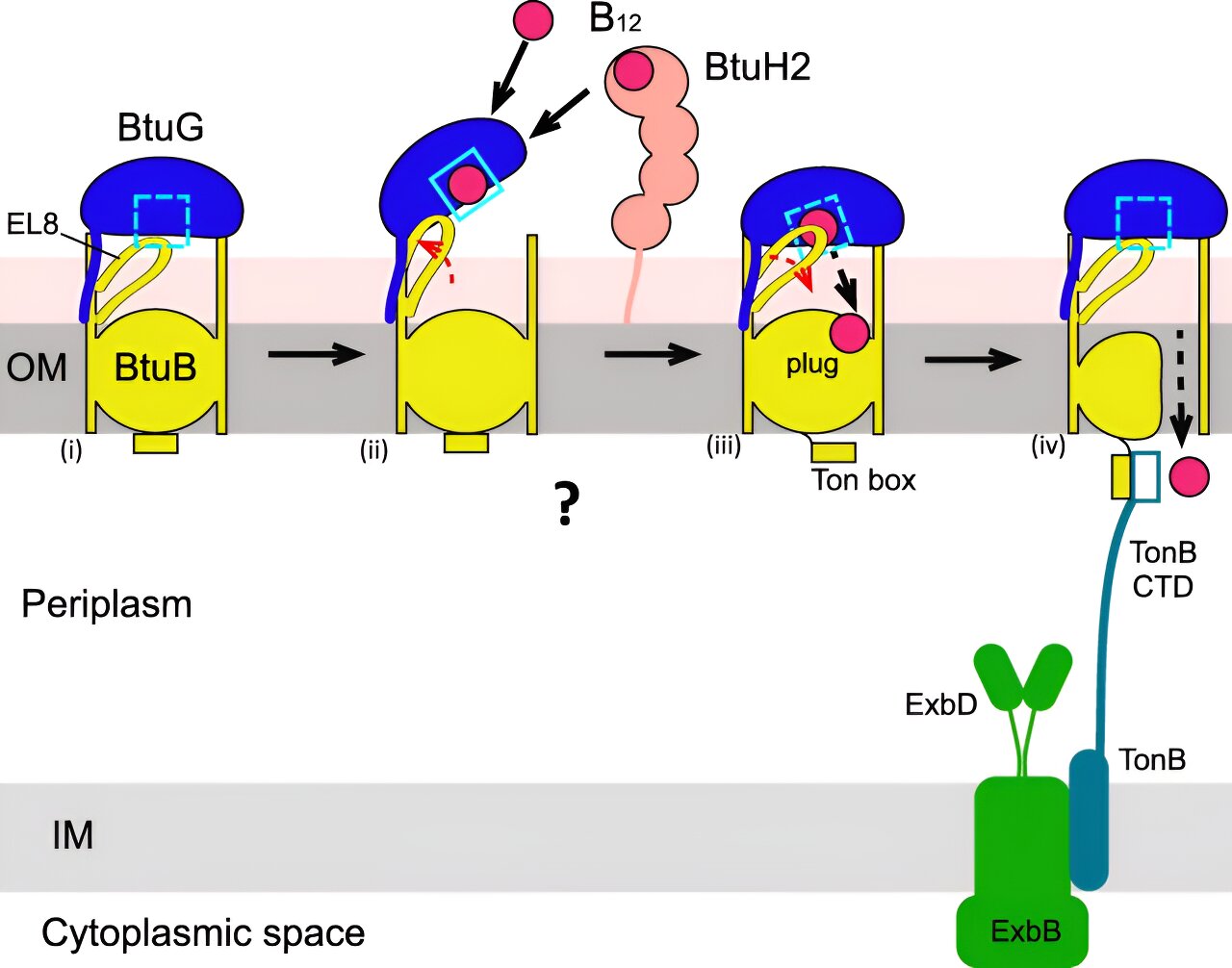

But wait, there’s more! These bacteriophages are not just any viruses; they are satellite viruses that rely on other helper viruses to complete their life cycle. These satellite viruses need their helpers to build their protein shells or replicate their DNA. And now, the study reveals that they take their relationship to the next level by attaching themselves to their helper virus’s “neck,” where the capsid meets the tail.

Believe it or not, this groundbreaking discovery almost slipped through the cracks. A group of undergraduates stumbled upon it while analyzing bacteriophages from environmental samples. Initially, they thought it was contamination, but further experiments confirmed that they had stumbled upon something extraordinary. Electron microscopy imaging later revealed the presence of helper viruses, with 80 percent of them having a satellite virus attached at the neck. Some helpers even had remnants of past attachments, like bite marks!

But that’s not all. The researchers also analyzed the genomes of these vampiric viruses, their helpers, and their hosts. They discovered that most satellites have a gene that allows them to integrate into the host cell’s genetic material. However, there was one exception. The satellite named MiniFlayer lacks this integration gene, which means it must stay close to its helper, MindFlayer, when entering a host cell.

Why do they attach? According to senior author Ivan Erill, it ensures that they enter the cell at the same time. This attachment between MiniFlayer and MindFlayer may have been going on for at least 100 million years, as suggested by further bioinformatics analysis.

The implications of this discovery are mind-boggling. The researchers hope that their findings will inspire further exploration into this unexpected phenomenon, shedding light on phage sequencing contamination and expanding our understanding of these satellite-helper systems.

So, the next time you come across a bacteriophage, remember that it might not be alone. It could be part of a fascinating satellite-helper system that has been hiding in plain sight all along.

Curious to learn more? Check out the study published in The ISME Journal.