Prepare to be shocked: microscopic plastic particles have been discovered in the fats and lungs of two-thirds of marine mammals. This groundbreaking study conducted by a graduate student sheds light on the alarming presence of polymer particles and fibers in these animals. It suggests that microplastics can actually travel beyond the digestive tract and lodge themselves in the tissues.

Get ready for the shocking details: this study, set to be published in the October 15th edition of Environmental Pollution, has just been released online. The potential harm caused by embedded microplastics in marine mammals is still unknown, but other studies have implicated plastics as possible hormone mimics and endocrine disruptors.

“This is an additional burden on top of everything else they face: climate change, pollution, noise. Now, not only are they ingesting plastic and dealing with the large pieces in their stomachs, but it’s also being internalized,” explains Greg Merrill Jr., a fifth-year graduate student at Duke University Marine Lab. “A portion of their mass is now plastic.”

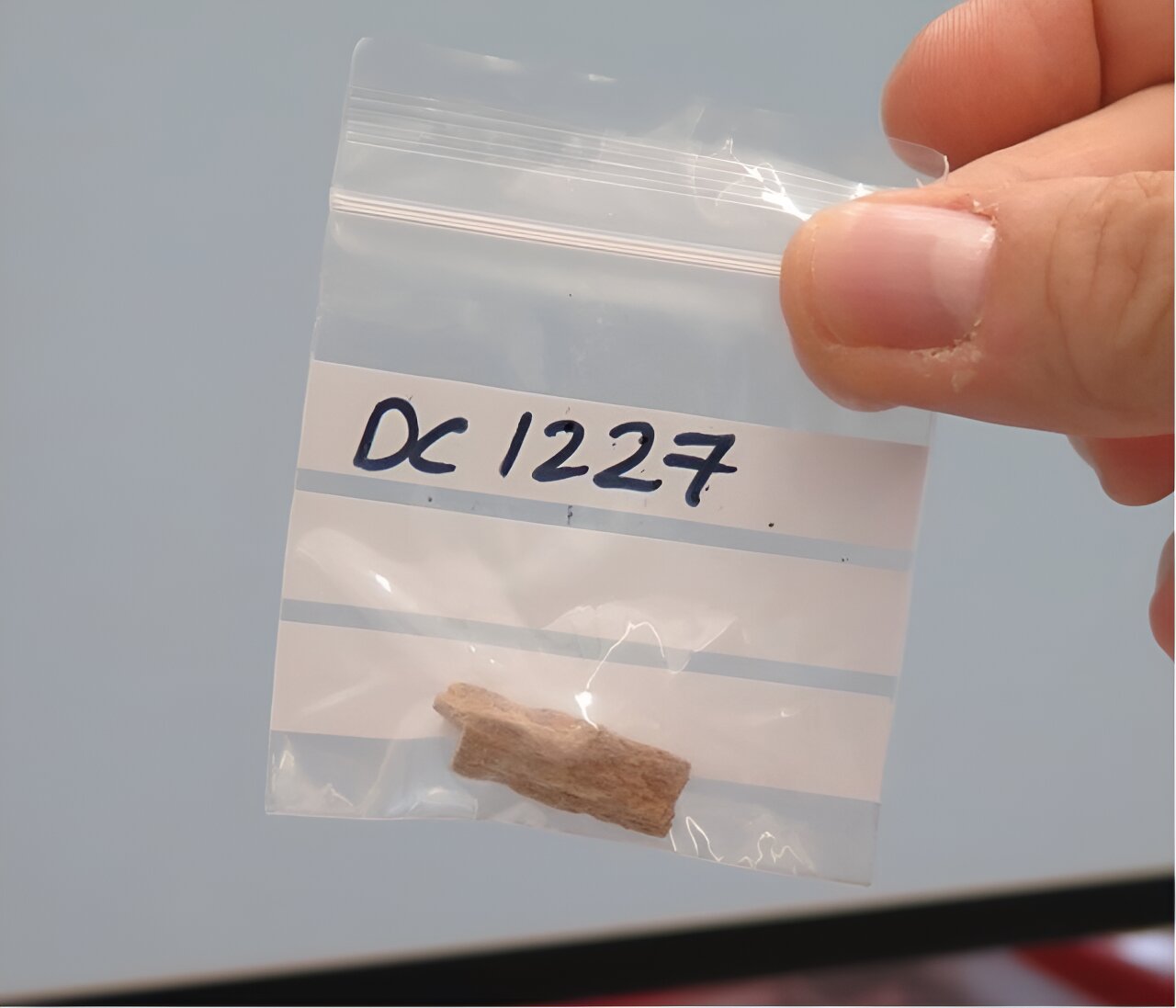

The samples used in this study were collected from 32 stranded or subsistence-harvested animals between 2000 and 2021 in Alaska, California, and North Carolina. The data includes twelve different species, with even a bearded seal found to have plastic in its tissues.

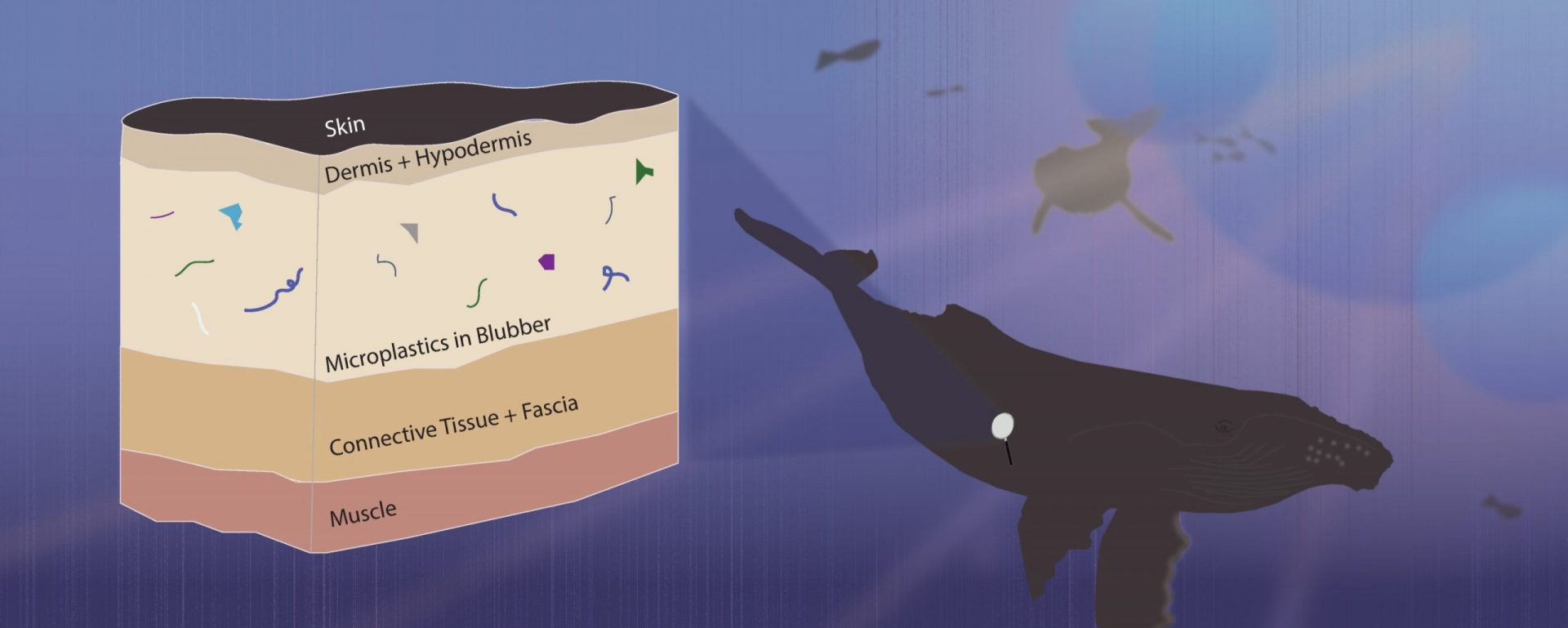

Plastics are irresistibly attracted to fats, making them lipophilic. This explains why they easily find their way into blubber, the sound-producing melon on a toothed whale’s forehead, and the fat pads along the lower jaw that focus sound to the whales’ internal ears. The study examined these three types of fats, as well as the lungs, and found plastics in all four tissues.

The plastic particles identified in the tissues ranged in size from 198 to 537 microns, with the average being larger than a human hair’s diameter of 100 microns. Merrill emphasizes that aside from the potential chemical threat, plastic pieces can also cause tearing and abrasion of tissues.

“Now that we know plastic is present in these tissues, we’re investigating the potential metabolic impact,” Merrill reveals. For the next phase of his dissertation research, Merrill plans to conduct toxicology tests on plastic particles using cell lines grown from biopsied whale tissue.

Polyester fibers, a common byproduct of laundry machines, were the most frequently found in tissue samples, along with polyethylene, a component of beverage containers. Interestingly, blue plastic was the most prevalent color found in all four types of tissue.

A recent paper published in Nature Communications estimated that a filter-feeding blue whale off the Pacific Coast of California could be ingesting a staggering 95 pounds of plastic waste per day as it catches tiny creatures in the water column. Whales and dolphins that prey on fish and larger organisms may also be accumulating plastic from their prey, according to Merrill.

“We haven’t done the math, but it’s likely that most microplastics pass through the gut and are excreted. However, a portion of it ends up in the animals’ tissues,” Merrill explains.

“This just highlights the widespread presence of ocean plastics and the magnitude of this problem,” Merrill concludes. “Some of these samples date back to 2001. It’s been happening for at least 20 years.”