“Back-to-school” season means more than just buying school supplies and figuring out bus routes. It also means dealing with earaches, a common issue among children. Typically, doctors treat these infections with antibiotics, but there’s a problem – children often don’t complete the full course of antibiotics, which can lead to resistance. However, researchers have now developed a groundbreaking solution that’s unlikely to generate resistance. They’ve created a single-use nanoscale system that can kill off the bacteria causing ear infections, and it could potentially be applied as a gel in the future.

The researchers will present their groundbreaking results today at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

“We initially got the idea by looking at household bleach. Surprisingly, bacteria haven’t developed resistance to this cleaner, even though it has been used for centuries,” says Rong Yang, Ph.D., the project’s principal investigator.

However, Yang emphasizes that using bleach to treat infections is not safe. The bleach sold in stores is highly concentrated and caustic. But when used in controlled, low concentrations, the active ingredient in bleach is considered compatible with living tissue.

Realizing the potential of bleach’s active ingredient to combat antibiotic resistance, the researchers at Cornell University decided to focus on a common childhood problem: acute ear infections. These infections affect over 95% of children in the U.S. and typically require a course of antibiotics. However, these antibiotics can have side effects, leading some families to stop the medication prematurely. Unfortunately, improper use of antibiotics contributes to the development of antibiotic resistance, a major global health concern according to the World Health Organization.

Bacteria have difficulty fighting certain substances, including hypochloric acid found in bleach. This acid belongs to a family of compounds called hypohalous acids, which bacteria haven’t developed significant resistance to. These acids damage microbial cells in various ways, making them effective against bacteria.

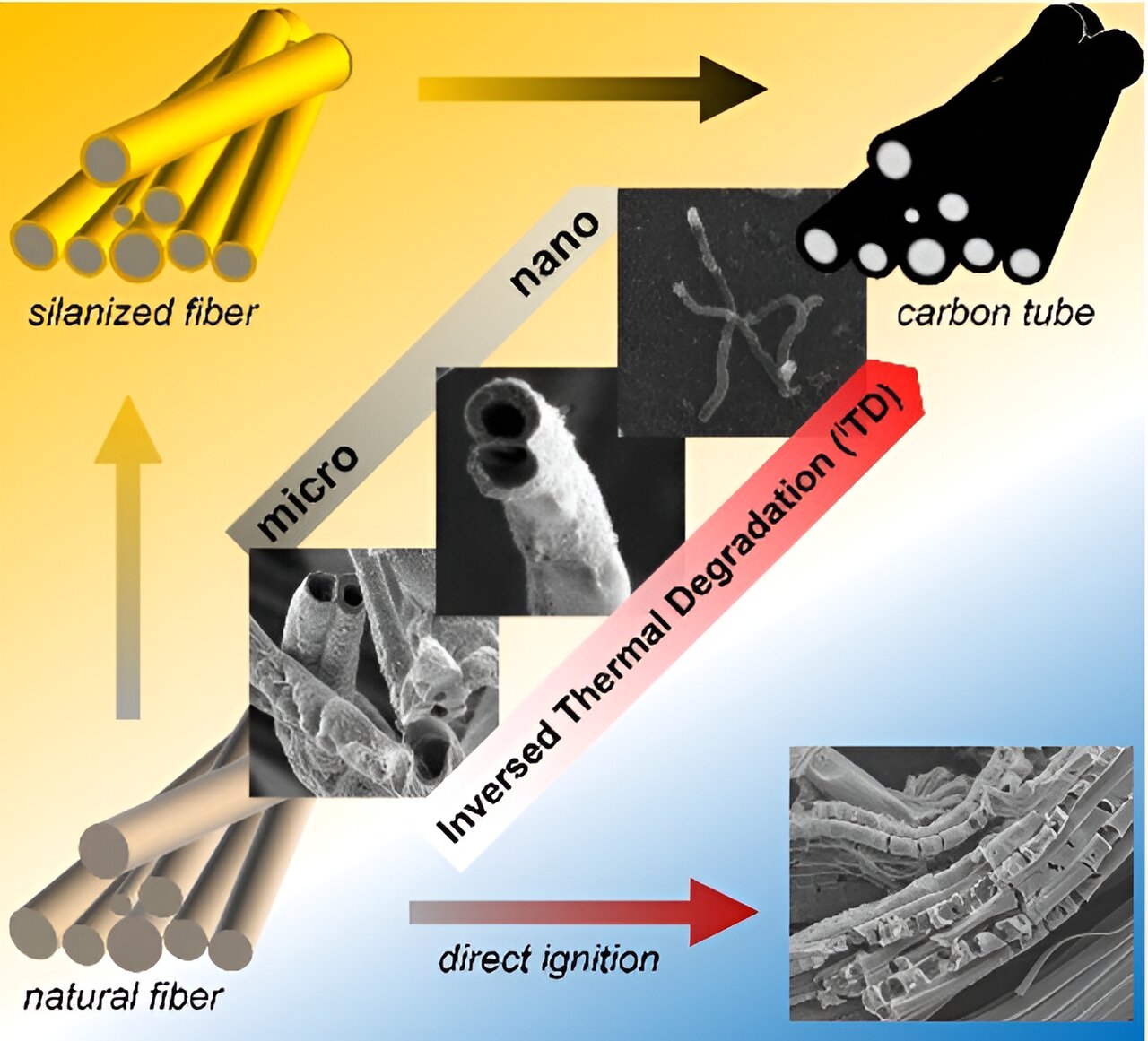

Building on this knowledge, Yang and her colleagues developed nanowires made of vanadium pentoxide, inspired by an enzyme found in giant kelp. These nanowires produce a bleach-like compound called hypobromous acid in the presence of bacteria that cause ear infections. The rod-like shape of the nanowires helps keep them in place, preventing them from diffusing into body fluids.

In tests on chinchillas, which are susceptible to the same pathogens as human children, the researchers successfully eliminated most of the bacteria causing ear infections. The animals’ inflamed eardrums returned to normal after treatment with the nanowires. Additionally, tests on healthy animals showed that the treatment did not interfere with hearing.

Initially, the researchers injected the nanowires directly into the middle ear. However, they later developed a less invasive method for delivering the treatment. By coating the nanowires with peptides that can transport small particles across the eardrum, they were able to deliver the treatment topically as a gel deposited into the ear canal. The nanowires passed through the intact tissue, providing an effective and practical solution.

Currently, the researchers are examining whether this system is effective against other bacteria that cause ear infections. They are also exploring ways to make the nanowires stay in place for longer periods, potentially preventing recurrent infections.

“If the bacteria return, the system could restart, so children wouldn’t need repeated antibiotics, which would help prevent the development of antibiotic resistance,” says Yang.