Step back in time to the 1840s at the Vienna General Hospital’s maternity clinic, the largest in the world at that time. Something strange and perplexing was happening. The clinic had two wards: Ward One and Ward Two. If you were a pregnant woman admitted to Ward One, your chances of survival were only 29 percent. But if you were admitted to Ward Two, your chances of dying dropped dramatically to just 3 percent. What could possibly explain this stark difference?

During the 18th and 19th centuries, a deadly infection known as childbed fever, or puerperal fever, plagued hospitals with maternity wards. It struck women shortly after childbirth, causing excruciating abdominal pain, fever, debility, and often death. At the time, the concept of germ theory had not yet been established, making it difficult for physicians to understand how the disease spread.

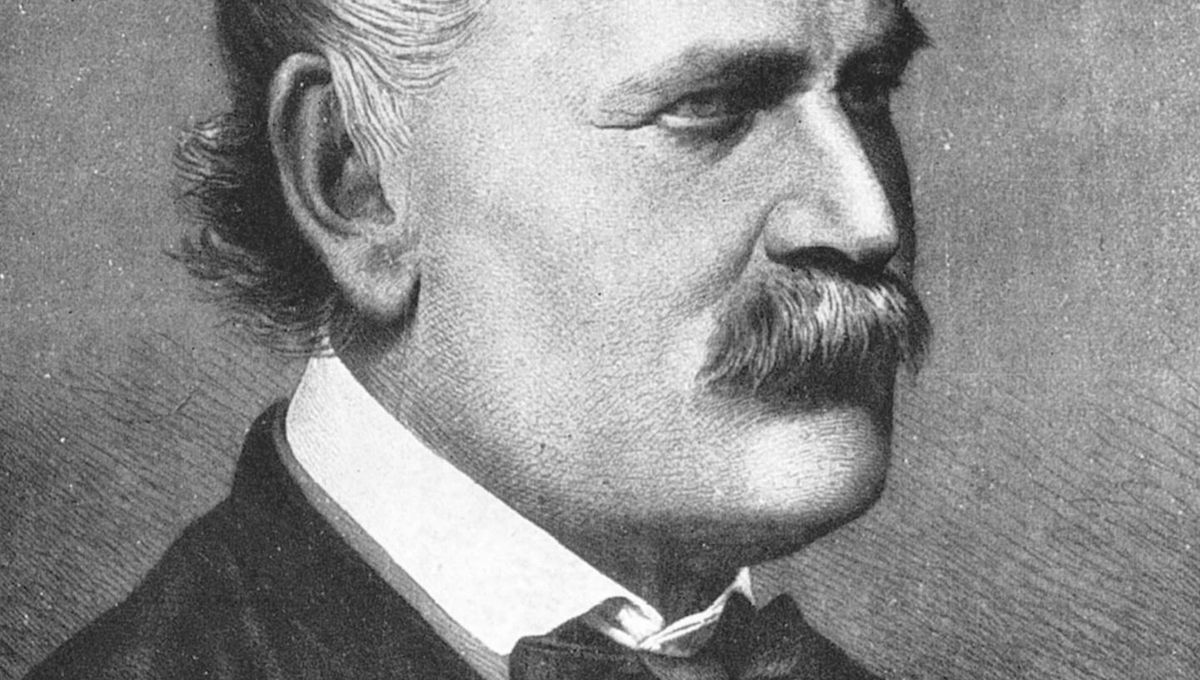

Enter Ignaz Semmelweis, an assistant physician at the Vienna General Hospital. Semmelweis noticed the alarming discrepancy in mortality rates between the two wards and made a groundbreaking observation. Ward One was managed by medical students, while Ward Two was overseen by trainee midwives. To test his theory, Semmelweis had the two wards swap staff, and the results were chilling. The high mortality rates followed the medical students like grim reapers.

Another piece of the puzzle fell into place when a professor of forensic medicine died after a student accidentally cut his finger during an autopsy. Semmelweis noticed that the sepsis that killed the professor left similar signs in the bodies of women who died from childbed fever.

Haunted by this revelation, Semmelweis concluded that the medical students, who often went straight from autopsies to attending to pregnant women without proper handwashing, were unknowingly transmitting infectious matter. In May 1847, he implemented a policy mandating handwashing with chlorinated water for all staff. The mortality rates in both wards plummeted.

However, Semmelweis faced opposition from colleagues who believed the deaths were caused by miasma, or bad air. Frustrated, he resigned and moved to Budapest, where he continued his handwashing practices at St Rochus Hospital with the same positive results.

Despite publishing a book in 1861 explaining his views on childbed fever, Semmelweis faced rejection and eventually fell into obscurity. He became bitter and unstable, ultimately being confined to an asylum until his death at the age of 47.

Semmelweis’s story serves as a reminder that even groundbreaking scientific ideas can be overlooked due to established traditions. However, Semmelweis himself played a role in his own rejection, as he was known for his arrogance and difficult personality. It wasn’t until Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur’s research on bacteria as causal agents of disease that Semmelweis’s work gained greater recognition.

To delve into more fascinating stories, don’t forget to check out our free eBook, “Common Medical Myths And Misunderstandings.”