Plastic pollution is not just an environmental concern, it’s a ticking time bomb. Microplastics, those tiny pieces of plastic, have infiltrated every corner of our planet, from the depths of our oceans to the very air we breathe. Now, a groundbreaking study has shed light on the potential harm these microplastics could be causing to our bodies.

Led by the brilliant Professor Jaime Ross from the University of Rhode Island, a team of researchers set out to investigate how microplastics accumulate in the brains of mammals and the possible consequences. To do this, they exposed mice to drinking water contaminated with varying concentrations of microplastics over a three-week period.

The results were alarming. The team discovered signs of inflammation in the brains and livers of the mice, as well as changes in their behavior. These behavioral changes were particularly pronounced in older mice, resembling symptoms seen in patients with dementia.

“To us, this was striking,” said Ross. “These were not high doses of microplastics, but in only a short period of time, we saw these changes.” However, Ross emphasized that there are still many unanswered questions about how microplastics cause these effects. Are we more susceptible to inflammation as we age? Can our bodies effectively eliminate these toxins? Do our cells respond differently to these harmful particles?

Further analysis revealed that the microplastic particles had accumulated in every major organ of the mice’s bodies, even with such a short exposure. This is a sobering thought, especially considering recent research suggesting that each of us could be inhaling a credit card’s worth of plastic every week.

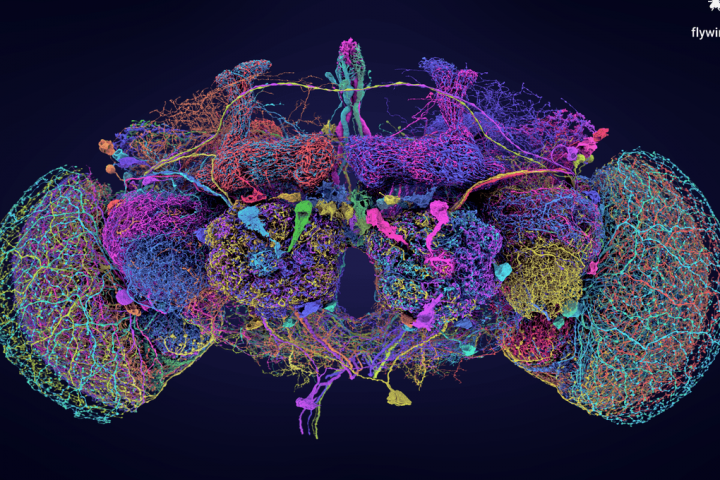

While it was expected that microplastics would be detected in organs like the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and kidneys, the team made a startling discovery. Microplastics had managed to breach the brain’s protective barrier, known as the blood-brain barrier, and infiltrate deep into its tissues. This contradicts previous research that showed microplastics could cross the blood-brain barrier in as little as two hours.

Once inside the brain, microplastics seemed to affect the levels of a crucial protein called GFAP, which is associated with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and depression. Ross expressed surprise at this finding, stating, “We were very surprised to see that the microplastics could induce altered GFAP signaling.”

This study is just the beginning. As microplastics continue to contaminate even the most remote parts of our planet, it is crucial that we understand the full extent of their impact on our health. Research like this is more urgent than ever before.

The findings of this groundbreaking study have been published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.