In a groundbreaking study, researchers have used a new method called FitCoal to analyze the likelihood of present-day genome sequences and project human genomic variation backwards in time. The results are astonishing, revealing a massive crash in genetic diversity during the transition between the early and middle Pleistocene.

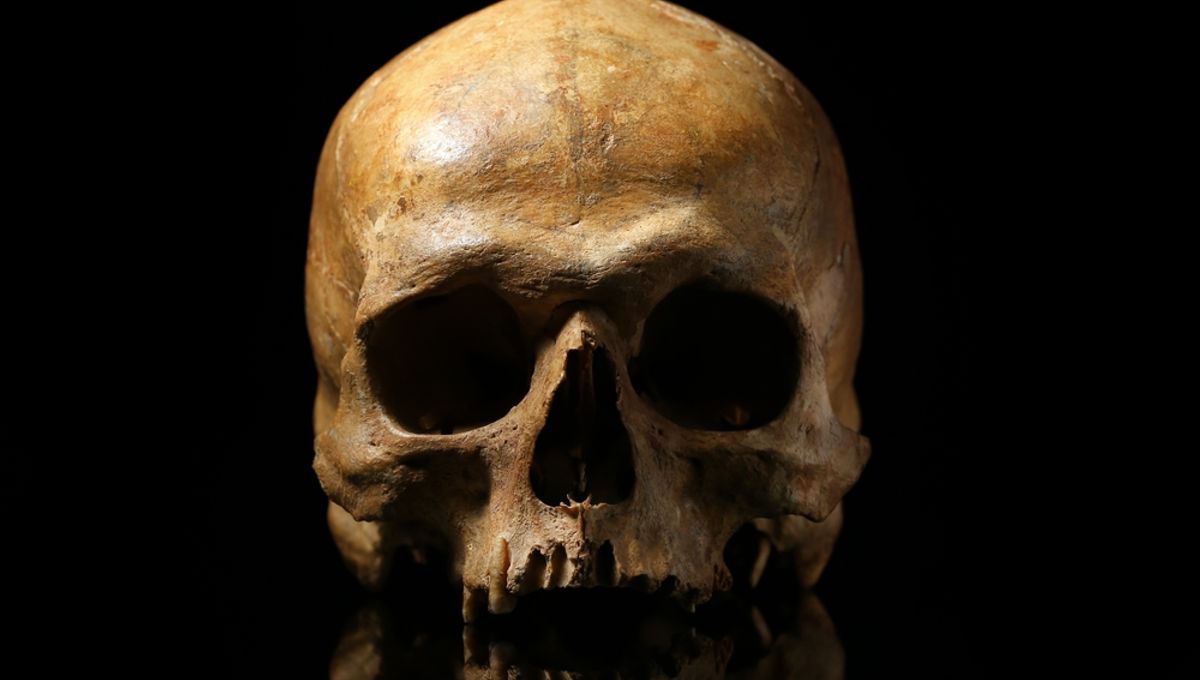

The study authors explain that our human ancestors went through a severe population bottleneck, with only about 1,280 breeding individuals surviving between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago. This bottleneck lasted for approximately 117,000 years and brought our ancestors dangerously close to extinction.

The researchers further reveal that this catastrophic event wiped out nearly 98.7 percent of the ancestral human population. Not only did it drastically reduce our numbers, but it also increased inbreeding among our ancestors, contributing to the significant loss in present-day human genetic diversity.

So, what caused this devastating die-off? The researchers believe that changes in the global climate played a significant role. Short-term glaciations became longer-lasting, leading to a drop in ocean temperatures, prolonged drought, and the loss of many species that humans relied on for food. It wasn’t until 813,000 years ago that populations finally began to recover, thanks to the mastery of fire and the return of warmer temperatures.

Interestingly, the researchers also discovered that this population bottleneck coincided with a speciation event. Two ancestral chromosomes fused to form what we now know as chromosome 2 in modern humans. This finding suggests that the last common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans may have emerged during this period of severe population decline.

Senior author Giorgio Manzi explains that this bottleneck in the Early Stone Age could explain the gap in the African and Eurasian fossil records. The proposed time period aligns with a significant loss of fossil evidence.

However, some researchers argue that fossil records from that time period suggest humans were widespread both inside and outside of Africa. They propose that whatever caused the bottleneck may have had limited effects on human populations outside the H. sapiens lineage or that its effects were short-lived.

The study authors acknowledge that their genetic data still need to be corroborated against archaeological records and that there are gaps in their findings. They raise intriguing questions about where these individuals lived, how they survived the catastrophic climate changes, and whether natural selection during the bottleneck accelerated the evolution of the human brain.

This groundbreaking study, published in the journal Science, provides valuable insights into our ancient past and the challenges our ancestors faced.